British Union Of Fascists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist

The BUF claimed 50,000 members at one point, and the '' Daily Mail'', running the headline "Hurrah for the Blackshirts!", was an early supporter. The first Director of Propaganda, appointed in February 1933, was

The BUF claimed 50,000 members at one point, and the '' Daily Mail'', running the headline "Hurrah for the Blackshirts!", was an early supporter. The first Director of Propaganda, appointed in February 1933, was

"British Union of Fascists (act. 1932–1940)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 (Accessed 5 February 2014) *

Resistance to fascism

', Glasgow Digital Library (Accessed 6 February 2014) Richard Griffiths, ''Fellow Travellers of the Right: British Enthusiasts for Nazi Germany''. London: Constable, 1980. p.52 The names are from MI5 Report. 1 August 1934. PRO HO 144/20144/110. (Cited in Thomas Norman Keeley

Blackshirts Torn: inside the British Union of Fascists, 1932- 1940

' p.26) (Accessed 6 February 2014) ** His wife Lady Russell was also a member. * Edward Russell, 26th Baron de Clifford, was a member of the House of Lords. * Hastings Russell, 12th Duke of Bedford, was a member of the House of Lords. * Alexander Raven Thomson was the party's Director of Public Policy. *

* The

* The

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, following the start of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the party was proscribed

Proscription ( la, proscriptio) is, in current usage, a 'decree of condemnation to death or banishment' (''Oxford English Dictionary'') and can be used in a political context to refer to state-approved murder or banishment. The term originated ...

by the British government and in 1940 it was disbanded.

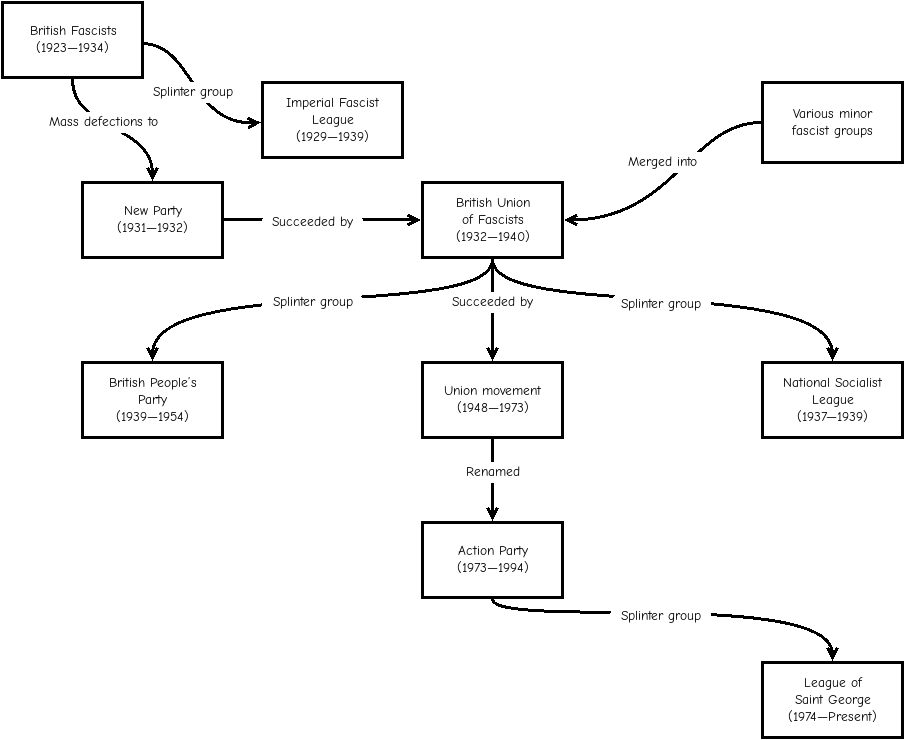

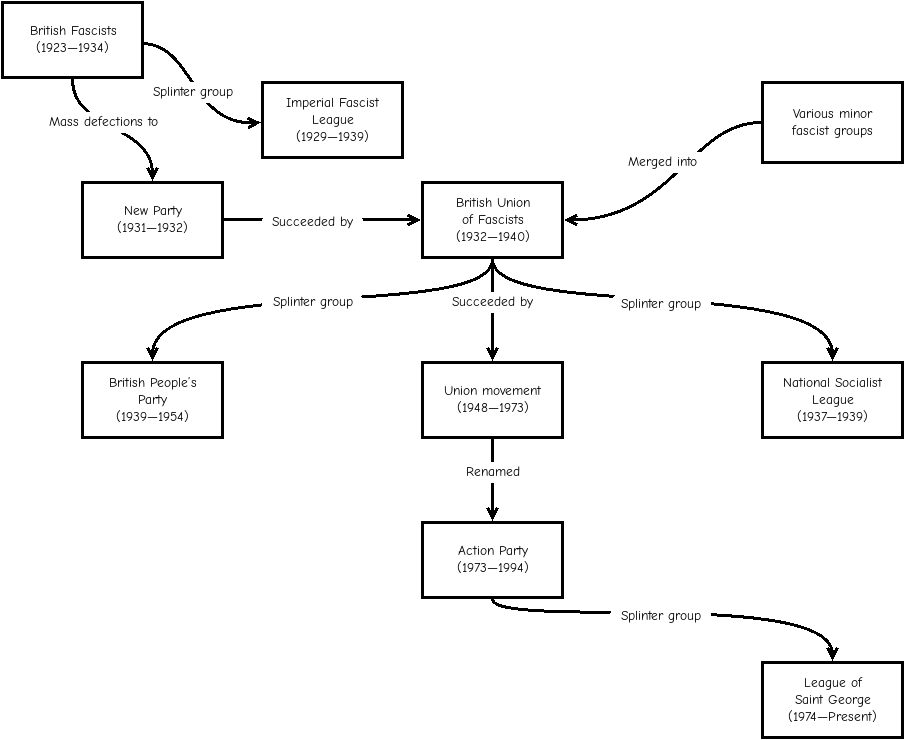

The BUF emerged in 1932 from the electoral defeat of its antecedent, the New Party, in the 1931 general election. The BUF's foundation was initially met with popular support, and it attracted a sizeable following, with the party claiming 50,000 members at one point. The press baron Lord Rothermere

Viscount Rothermere, of Hemsted in the county of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1919 for the press lord Harold Harmsworth, 1st Baron Harmsworth. He had already been created a baronet, of Horsey in th ...

was a notable early supporter. As the party became increasingly radical, however, support declined. The Olympia Rally of 1934, in which a number of anti-fascist protestors were attacked by the paramilitary wing of the BUF, the Fascist Defence Force

The Fascist Defence Force (FDF) was the paramilitary section of the British Union of Fascists (BUF).Martin Pugh, Hurrah For The Blackshirts!: Fascists and Fascism in Britain Between the Wars, pp. 133-135, Random House

It was established in August ...

, isolated the party from much of its following. The party's embrace of Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

-style anti-semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in 1936 led to increasingly violent anti-fascist confrontations, notably the 1936 Battle of Cable Street

The Battle of Cable Street was a series of clashes that took place at several locations in the inner East End, most notably Cable Street, on Sunday 4 October 1936. It was a clash between the Metropolitan Police, sent to protect a march by mem ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

's East End. The Public Order Act 1936

The Public Order Act 1936 (1 Edw. 8 & 1 Geo. 6 c. 6) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed to control extremist political movements in the 1930s such as the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Largely the work of Home Office ci ...

, which banned political uniform

A number of political movements have involved their members wearing uniforms, typically as a way of showing their identity in marches and demonstrations. The wearing of political uniforms has tended to be associated with radical political belie ...

s and responded to increasing political violence, had a particularly strong effect on the BUF whose supporters were known as "Blackshirts" after the uniforms they wore.

Growing British hostility towards Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, with which the British press persistently associated the BUF, further contributed to the decline of the movement's membership. It was finally banned by the British government on 23 May 1940 after the start of the Second World War, amid suspicion that its remaining supporters might form a pro-Nazi " fifth column". A number of prominent BUF members were arrested and interned under Defence Regulation 18B

Defence Regulation 18B, often referred to as simply 18B, was one of the Defence Regulations used by the British Government during and before the Second World War. The complete name for the rule was Regulation 18B of the Defence (General) Regula ...

.

History

Background

Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

was the youngest elected Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

MP before crossing the floor

In parliamentary systems, politicians are said to cross the floor if they formally change their political affiliation to a different political party than which they were initially elected under (as is the case in Canada and the United Kingdom). ...

in 1922, joining first Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

and, shortly afterward, the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

. He became Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is a ministerial office in the Government of the United Kingdom. The position is the second highest ranking minister in the Cabinet Office, immediately after the Prime Minister, and senior to the Minist ...

in Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government, advising on rising unemployment.

In 1930, Mosley issued his Mosley Memorandum, which fused protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

with a proto-Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

programme of policies designed to tackle the problem of unemployment, and he resigned from the Labour Party soon after, in early 1931, when the plans were rejected. He immediately formed the New Party, with policies based on his memorandum. The party won 16% of the vote at a by-election in Ashton-under-Lyne

Ashton-under-Lyne is a market town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England. The population was 45,198 at the 2011 census. Historically in Lancashire, it is on the north bank of the River Tame, in the foothills of the Pennines, east of Manche ...

in early 1931; however, it failed to achieve any other electoral success.

During 1931, the New Party became increasingly influenced by fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. The following year, after a January 1932 visit to Benito Mussolini in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Mosley's own conversion to fascism was confirmed. He wound up the New Party in April, but preserved its youth movement, which would form the core of the BUF, intact. He spent the summer that year writing a fascist programme, ''The Greater Britain'', and this formed the basis of policy of the BUF, which was launched on 1 October 1932.Thorpe, Andrew. (1995) ''Britain In The 1930s'', Blackwell Publishers,

Early success and growth

The BUF claimed 50,000 members at one point, and the '' Daily Mail'', running the headline "Hurrah for the Blackshirts!", was an early supporter. The first Director of Propaganda, appointed in February 1933, was

The BUF claimed 50,000 members at one point, and the '' Daily Mail'', running the headline "Hurrah for the Blackshirts!", was an early supporter. The first Director of Propaganda, appointed in February 1933, was Wilfred Risdon

Wilfred Risdon (28 January 1896 – 11 March 1967) was a British trade union organizer, a founder member of the British Union of Fascists and an antivivisection campaigner. His life and career encompassed coal mining, trade union work, First W ...

, who was responsible for organising all of Mosley's public meetings. Despite strong resistance from anti-fascists, including the local Jewish community

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, the Labour Party, the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

, and the Communist Party of Great Britain, the BUF found a following in the East End of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, where in the London County Council

London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today kno ...

elections of March 1937, it obtained reasonably successful results in Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in the East End of London northeast of Charing Cross. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the Green, much of which survives today as Bethnal Green Gardens, beside Cambridge Heath Road. By ...

, Shoreditch, and Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through ...

, polling almost 8,000 votes, although none of its candidates was elected. The BUF did elect a few councillors at local government level during the 1930s (including Charles Bentinck Budd (Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Ho ...

, Sussex), 1934; Ronald Creasy (Eye, Suffolk

Eye () is a market town and civil parish in the north of the English county of Suffolk, about south of Diss, Norfolk, Diss, north of Ipswich and south-west of Norwich. The population in the 2011 Census of 2,154 was estimated to be 2,361 in 2 ...

), 1938) but did not win any parliamentary seats. Two former members of the BUF, Major Sir Jocelyn Lucas

Major Sir Jocelyn Morton Lucas, 4th Baronet, (27 August 1889 – 2 May 1980) was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician. He was elected as the Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament for Portsmouth ...

and Harold Soref

Harold Benjamin Soref (18 December 1916—14 March 1993) was a Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom for Ormskirk, Lancashire, first elected at the 1970 general election. He subsequently lost the seat to Labour in Feb ...

, were later elected as Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MPs).

Having lost the funding of newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere

Viscount Rothermere, of Hemsted in the county of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1919 for the press lord Harold Harmsworth, 1st Baron Harmsworth. He had already been created a baronet, of Horsey in th ...

that it had previously enjoyed, at the 1935 general election the party urged voters to abstain, calling for "Fascism Next Time". There never was a "next time" as the next general election was not held until July 1945, five years after the dissolution of the BUF.

Towards the middle of the 1930s, the BUF's violent clashes with opponents began to alienate some middle-class supporters, and membership decreased. At the Olympia rally in London, in 1934, BUF stewards violently ejected anti-fascist disrupters, and this led the '' Daily Mail'' to withdraw its support for the movement. The level of violence shown at the rally shocked many, with the effect of turning neutral parties against the BUF and contributing to anti-fascist support. One observer claimed: "I came to the conclusion that Mosley was a political maniac, and that all decent English people must combine to kill his movement."

In Belfast in April 1934 an autonomous wing of the party in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

called the "Ulster Fascists" was founded. The branch was a failure and became virtually extinct after less than a year in existence. It had ties with the Blueshirts

The Army Comrades Association (ACA), later the National Guard, then Young Ireland and finally League of Youth, but best known by the nickname the Blueshirts ( ga, Na Léinte Gorma), was a paramilitary organisation in the Irish Free State, founded ...

in the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between ...

and voiced support for a United Ireland

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

, describing the partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. ...

as "an insurmountable barrier to peace, and prosperity in Ireland". Its logo was a fasces on a Red Hand of Ulster

The Red Hand of Ulster ( gle, Lámh Dhearg Uladh), also known as the Red Hand Uí Néill, is a symbol used in heraldry to denote the Irish province of Ulster and the Northern Uí Néill in particular. However, it has also been used by other I ...

.

Decline and legacy

The BUF became more antisemitic over 1934–35 owing to the growing influence of Nazi sympathisers within the party, such asWilliam Joyce

William Brooke Joyce (24 April 1906 – 3 January 1946), nicknamed Lord Haw-Haw, was an American-born fascist and Nazi propaganda broadcaster during the Second World War. After moving from New York to Ireland and subsequently to England, ...

and John Beckett, which provoked the resignation of members such as Dr. Robert Forgan. This anti-semitic emphasis and these high-profile resignations resulted in a significant decline in membership, dropping to below 8,000 by the end of 1935, and, ultimately, Mosley shifted the party's focus back to mainstream politics. There were frequent and continuous violent clashes between BUF party members and anti-fascist protesters, most famously at the Battle of Cable Street

The Battle of Cable Street was a series of clashes that took place at several locations in the inner East End, most notably Cable Street, on Sunday 4 October 1936. It was a clash between the Metropolitan Police, sent to protect a march by mem ...

in October 1936, when organised anti-fascists prevented the BUF from marching through Cable Street. However, the party later staged other marches through the East End without incident, albeit not on Cable Street itself.

BUF support for Edward VIII and the peace campaign to prevent a second World War

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

saw membership and public support rise once more.Richard C. Thurlow. ''Fascism in Britain: from Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts to the National Front''. 2nd edition. New York, New York, USA: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2006. p. 94. The government was sufficiently concerned by the party's growing prominence to pass the Public Order Act 1936

The Public Order Act 1936 (1 Edw. 8 & 1 Geo. 6 c. 6) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed to control extremist political movements in the 1930s such as the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

Largely the work of Home Office ci ...

, which banned political uniform

A number of political movements have involved their members wearing uniforms, typically as a way of showing their identity in marches and demonstrations. The wearing of political uniforms has tended to be associated with radical political belie ...

s and required police consent for political marches.

In 1937, William Joyce and other Nazi sympathisers split from the party to form the National Socialist League

The National Socialist League (NSL) was a short-lived Nazi political movement in the United Kingdom immediately prior to the Second World War.

Formation

The NSL was formed in 1937 by William Joyce, John Beckett (politician), John Beckett and ...

, which quickly folded, with most of its members interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

. Mosley later denounced Joyce as a traitor and condemned him for his extreme anti-semitism. The historian Stephen Dorril revealed in his book ''Blackshirts'' that secret envoys from the Nazis had donated about £50,000 to the BUF.

By 1939, total BUF membership had declined to just 20,000. On 23 May 1940, the BUF was banned outright by the government via Defence Regulation 18B

Defence Regulation 18B, often referred to as simply 18B, was one of the Defence Regulations used by the British Government during and before the Second World War. The complete name for the rule was Regulation 18B of the Defence (General) Regula ...

and Mosley, along with 740 other fascists, was interned for much of the Second World War. After the war, Mosley made several unsuccessful attempts to return to politics, such as via the Union Movement

The Union Movement (UM) was a far-right political party founded in the United Kingdom by Oswald Mosley. Before the Second World War, Mosley's British Union of Fascists (BUF) had wanted to concentrate trade within the British Empire, but the Uni ...

.

Relationship with the suffragettes

Attracted by ‘modern’ fascist policies, such as ending the widespread practice of sacking women from their jobs on marriage, many women joined the Blackshirts – particularly in economically depressed Lancashire. Eventually women constituted one-quarter of the BUF's membership. In a January 2010 BBC documentary, ''Mother Was A Blackshirt'', James Maw reported that in 1914Norah Elam

Norah Elam, also known as Norah Dacre Fox (née Norah Doherty, 1878–1961), was a militant suffragette, anti-vivisectionist, feminist and fascist in the United Kingdom. Born at 13 Waltham Terrace in Dublin to John Doherty, a partner in a pape ...

was placed in a Holloway Prison

HM Prison Holloway was a closed category prison for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, until its closure in 2016.

Histor ...

cell with Emmeline Pankhurst for her involvement with the suffragette movement, and, in 1940, she was returned to the same prison with Diana Mosley, this time for her involvement with the fascist movement. Another leading suffragette, Mary Richardson, became head of the women's section of the BUF.

Mary Sophia Allen OBE was a former branch leader of the West of England Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). At the outbreak of the First World War, she joined the Women Police Volunteers, becoming the WPV Commandant in 1920. She met Mosley at the January Club in April 1932, going on to speak at the club following her visit to Germany, "to learn the truth about of the position of German womanhood".

The BBC report described how Elam's fascist philosophy grew from her suffragette experiences, how the British fascist movement became largely driven by women, how they targeted young women from an early age, how the first British fascist movement was founded by a woman, and how the leading lights of the suffragettes had, with Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

, founded the BUF.

Mosley's electoral strategy had been to prepare for the election after 1935, and in 1936 he announced a list of BUF candidates for that election, with Elam nominated to stand for Northampton. Mosley accompanied Elam to Northampton to introduce her to her electorate at a meeting in the Town Hall. At that meeting Mosley announced that "he was glad indeed to have the opportunity of introducing the first candidate, and ... herebykilled for all time the suggestion that National Socialism proposed putting British women back into the home; this is simply not true. Mrs Elam e went onhad fought in the past for women's suffrage ... and was a great example of the emancipation of women in Britain."

Former suffragettes were drawn to the BUF for a variety of reasons. Many felt the movement's energy reminded them of the suffragettes, while others felt the BUF's economic policies would offer them true equality – unlike its continental counterparts, the movement insisted it would not require women to return to domesticity and that the corporatist

Corporatism is a Collectivism and individualism, collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by Corporate group (sociology), corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guil ...

state would ensure adequate representation for housewives, while it would also guarantee equal wages for women and remove the marriage bar that restricted the employment of married women. The BUF also offered support for new mothers (due to concerns of falling birth rates), while also offering effective birth control, as Mosley believed it was not in the national interest to have a populace ignorant of modern scientific knowledge. While these policies were motivated more out of making the best use of women's skills in state interest than any kind of feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, it was still a draw for many suffragettes.

Prominent members and supporters

Despite the short period of its operation the BUF attracted prominent members and supporters. These included: *William Edward David Allen

William Edward David Allen (6 January 1901 – 18 September 1973) was a British scholar, Foreign Service officer, politician and businessman, best known as a historian of the South Caucasus—notably Georgia. He was closely involved in the polit ...

was previously Unionist Member of Parliament for Belfast West. Material in the National Archive shows that Allen acted as an MI5 agent within the BUF.

* John Beckett was previously Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

Member of Parliament for Peckham.

* Frank Bossard was an officer in the RAF and, after the war, a Soviet spy.

* Patrick Boyle, 8th Earl of Glasgow

Patrick James Boyle, 8th Earl of Glasgow, (18 June 1874 – 14 December 1963), was a Scottish nobleman and a far right political activist, involved with fascist parties and groups.

Royal Navy

Boyle was trained for a naval career at the cadet sh ...

was a member of the House of Lords.

* Malcolm Campbell

Major Sir Malcolm Campbell (11 March 1885 – 31 December 1948) was a British racing motorist and motoring journalist. He gained the world speed record on land and on water at various times, using vehicles called ''Blue Bird'', including a 1 ...

was a racing motorist and motoring journalist.

* A. K. Chesterton

Arthur Kenneth Chesterton (1 May 1899 – 16 August 1973) was a British far-right journalist and political activist. From 1933 to 1938, he was a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Disillusioned with Oswald Mosley, he left th ...

was a journalist.

* Lady Cynthia Curzon (known as 'Cimmie') was the second daughter of George Curzon, Lord Curzon of Kedleston, and the wife of Oswald Mosley until her death in 1933.

* Robert Forgan

Robert Forgan (10 March 1891 – 8 January 1976) was a British politician who was a close associate of Oswald Mosley.

Early life and medical career

The Scottish-born Forgan was the son of a Church of Scotland minister.Dorril, p. 151 Educated up ...

was previously Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

Member of Parliament for West Renfrewshire.Julie V. Gottlieb"British Union of Fascists (act. 1932–1940)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 (Accessed 5 February 2014) *

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

John Frederick Charles Fuller

Major-General John Frederick Charles "Boney" Fuller (1 September 1878 – 10 February 1966) was a senior British Army officer, military historian, and strategist, known as an early theorist of modern armoured warfare, including categorising p ...

was a military historian and strategist.

* Billy Fullerton was leader of the Billy Boys

"Billy Boys", also titled "The Billy Boys", is a loyalist song from Glasgow, sung to the tune of "Marching Through Georgia." It originated in the 1920s as the signature song of one of the Glasgow razor gangs led by Billy Fullerton and later b ...

gang from Glasgow.

* Arthur Gilligan was the captain of the England cricket team.

* Reginald Goodall

Sir Reginald Goodall (13 July 1901 – 5 May 1990) was an English conductor and singing coach noted for his performances of the operas of Richard Wagner and for conducting the premieres of several operas by Benjamin Britten.

Early life

Goodall ...

was an English conductor.

* Group Captain Louis Greig was a British naval surgeon

A naval surgeon, or less commonly ship's doctor, is the person responsible for the health of the ship's company aboard a warship. The term appears often in reference to Royal Navy's medical personnel during the Age of Sail.

Ancient uses

Speciali ...

, courtier and intimate of King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

.

* Jeffrey Hamm

Edward Jeffrey Hamm (15 September 1915 – 4 May 1992) was a leading British fascist and supporter of Oswald Mosley. Although a minor figure in Mosley's prewar British Union of Fascists, Hamm became a leading figure after the Second World War a ...

was a prominent member and later Mosley's personal secretary.

* Harold Sidney Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere

Harold Sidney Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere, (26 April 1868 – 26 November 1940) was a leading British newspaper proprietor who owned Associated Newspapers Ltd. He is best known, like his brother Alfred Harmsworth, later Viscount Northcl ...

, was the owner of the '' Daily Mail'' and a member of the House of Lords.

* Neil Francis Hawkins was leader of the Blackshirts.

* Josslyn Hay, 22nd Earl of Erroll, was a member of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

.

* William Joyce

William Brooke Joyce (24 April 1906 – 3 January 1946), nicknamed Lord Haw-Haw, was an American-born fascist and Nazi propaganda broadcaster during the Second World War. After moving from New York to Ireland and subsequently to England, ...

, later nicknamed 'Lord Haw-Haw', became naturalized as a German citizen and broadcast pro-Nazi propaganda from German territory.

* Ted "Kid" Lewis

Ted "Kid" Lewis (born Gershon Mendeloff; 28 October 1893 – 20 October 1970) was an English professional boxer who twice won the World Welterweight Championship (147 lb). Lewis is often ranked among the all-time greats, with ESPN ranking ...

was a Jewish boxing champion; he left the party after it became overtly anti-Semitic.

* David Freeman-Mitford, 2nd Baron Redesdale, was a member of the House of Lords. His wife, Lady Redesdale, and two of his daughters were also members:

** Diana Mitford

Diana, Lady Mosley (''née'' Freeman-Mitford; 17 June 191011 August 2003) was one of the Mitford sisters. In 1929 she married Bryan Walter Guinness, heir to the barony of Moyne, with whom she was part of the Bright Young Things social group o ...

(Lady Mosley, after her marriage to Sir Oswald Mosley in 1936)

** Unity Mitford

Unity Valkyrie Freeman-Mitford (8 August 1914 – 28 May 1948) was a British socialite, known for her relationship with Adolf Hitler. Both in Great Britain and Germany, she was a prominent supporter of Nazism, fascism and antisemitism, and belo ...

was an associate of Hitler.

* Tommy Moran was a BUF leader in Derby and later south Wales.

* St John Philby was an explorer, and the father of Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963 he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which had divulged British secr ...

.

* Sir Alliott Verdon Roe

Sir Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe OBE, Hon. FRAeS, FIAS (26 April 1877 – 4 January 1958) was a pioneer English pilot and aircraft manufacturer, and founder in 1910 of the Avro company. After experimenting with model aeroplanes, he made flight tr ...

was a pilot and businessman.

* Edward Frederick Langley Russell, 2nd Baron Russell of Liverpool, was a member of the House of Lords.Resistance to fascism

', Glasgow Digital Library (Accessed 6 February 2014) Richard Griffiths, ''Fellow Travellers of the Right: British Enthusiasts for Nazi Germany''. London: Constable, 1980. p.52 The names are from MI5 Report. 1 August 1934. PRO HO 144/20144/110. (Cited in Thomas Norman Keeley

Blackshirts Torn: inside the British Union of Fascists, 1932- 1940

' p.26) (Accessed 6 February 2014) ** His wife Lady Russell was also a member. * Edward Russell, 26th Baron de Clifford, was a member of the House of Lords. * Hastings Russell, 12th Duke of Bedford, was a member of the House of Lords. * Alexander Raven Thomson was the party's Director of Public Policy. *

Frank Cyril Tiarks

Frank Cyril Tiarks OBE (also known as F. C. Tiarks) (9 July 1874 – 7 April 1952) was an English banker.

Family

He was son of Henry Frederick Tiarks (23 December 1832 - 18 October 1911), banker, partner in J. Henry Schröder & Co. in Lond ...

, of German extraction, was a banker, a Director of the Bank of England and a prominent member of the Anglo-German Fellowship

The Anglo-German Fellowship was a membership organisation that existed from 1935 to 1939, and aimed to build up friendship between the United Kingdom and Germany. It was widely perceived as being allied to Nazism. Previous groups in Britain wit ...

.

** His wife, Emmy née Brödermann, was also a member.

* Frederick Toone

Sir Frederick Charles Toone (25 June 1868 - ) was a cricket administrator, who in 1929 became the second man ever to be knighted for cricket-related activities. Unusually for a man who achieved such eminence in the game, he never played cricket ...

was the manager of the England cricket team and Yorkshire Cricket Club.

* Henry Williamson

Henry William Williamson (1 December 1895 – 13 August 1977) was an English writer who wrote novels concerned with wildlife, English social history and ruralism. He was awarded the Hawthornden Prize for literature in 1928 for his book ''Tarka ...

was a writer, best known for his 1927 work ''Tarka the Otter

''Tarka the Otter: His Joyful Water-Life and Death in the Country of the Two Rivers'' is a novel by English writer Henry Williamson, first published in 1927 by G.P. Putnam's Sons with an introduction by the Hon. Sir John Fortescue. It won th ...

''.

In popular culture

Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a fourth television service ...

television serial '' Mosley'' (1998) portrayed the career of Oswald Mosley during his years with the BUF. The four-part series was based on the books ''Rules of the Game'' and ''Beyond the Pale'', written by his son Nicholas Mosley

Nicholas Mosley, 3rd Baron Ravensdale, 7th Baronet, MC, FRSL (25 June 1923 – 28 February 2017) was an English novelist.

Life

Mosley was born in London in 1923. He was the eldest son of Sir Oswald Mosley, 6th Baronet, a British politician, ...

.

* In the film ''It Happened Here

''It Happened Here'' (also known as ''It Happened Here: The Story of Hitler's England'') is a 1964 British black-and-white film written, produced and directed by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, who began work on the film as teenagers. The film ...

'' (1964), the BUF appears to be the ruling party of German-occupied Britain. A Mosley speech is heard on the radio in the scene before everyone goes to the movies.

* The first depiction of Mosley and the BUF in fiction occurred in Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxle ...

's novel ''Point Counter Point

''Point Counter Point'' is a novel by Aldous Huxley, first published in 1928. It is Huxley's longest novel, and was notably more complex and serious than his earlier fiction.

In 1998, the Modern Library ranked ''Point Counter Point'' 44th on ...

'' (1932), in which Mosley is depicted as Everard Webley, the murderous leader of the "BFF", the Brotherhood of Free Fascists; he comes to a nasty end.

* The BUF has been featured in several novels by Harry Turtledove

Harry Norman Turtledove (born June 14, 1949) is an American author who is best known for his work in the genres of alternate history, historical fiction, fantasy, science fiction, and mystery fiction. He is a student of history and completed hi ...

.

** In his alternative history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, alte ...

novel ''In the Presence of Mine Enemies

''In the Presence of Mine Enemies'' is a 2003 alternate history novel by American author Harry Turtledove, expanded from the eponymous short story. The title comes from the fifth verse of the 23rd Psalm. The novel depicts a world in which the Un ...

'', set in 2010 in a world in which the Nazis were triumphant, the BUF led by Prime Minister Charlie Lynton governs Britain. It is here that the first stirrings of the reform movement appear.

** In the ''Southern Victory

The ''Southern Victory'' series or Timeline-191 is a series of eleven alternate history novels by author Harry Turtledove, beginning with ''How Few Remain'' (1997) and published over a decade. The period addressed in the series begins during th ...

'' series, set in a reality in which the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

became independent and the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

(including the United States) won that reality's analogue of the First World War, the "Silver Shirts" (analogous to the BUF) entered into a coalition with the Conservatives who were led by Churchill with Mosley being appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer.

** The BUF and Mosley also appear as background influences in Turtledove's '' Colonization'' trilogy which follows the Worldwar

The Worldwar series is the fan name given to a series of eight alternate history science fiction novels by Harry Turtledove. Its premise is an alien invasion of Earth during World War II, and includes Turtledove's ''Worldwar'' tetralogy, as ...

tetralogy and is set in the 1960s.

* Pink Floyd's album ''The Wall

''The Wall'' is the eleventh studio album by the English progressive rock band Pink Floyd, released on 30 November 1979 by Harvest/EMI and Columbia/ CBS Records. It is a rock opera that explores Pink, a jaded rock star whose eventual self-imp ...

'' (1979) features BUF Blackshirts, particularly in the song "Waiting for the Worms" in which the protagonist of the conceptual album has a drug induced delusion that he is the leader of the resurgence of the BUF's Blackshirts.

* James Herbert

James John Herbert, OBE (8 April 1943 – 20 March 2013) was an English horror writer. A full-time writer, he also designed his own book covers and publicity. His books have sold 54 million copies worldwide, and have been translated into 34 l ...

's novel '' '48'' (1996) has a protagonist who is hunted by BUF Blackshirts in a devastated London after a biological weapon

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterroris ...

is released during the Second World War. The history of the BUF and Mosley is recapitulated.

* In Ken Follett

Kenneth Martin Follett, (born 5 June 1949) is a British author of thrillers and historical novels who has sold more than 160 million copies of his works.

Many of his books have achieved high ranking on best seller lists. For example, in the ...

's novel ''Night Over Water

''Night Over Water'' is a thriller novel written by author Ken Follett in 1991.

''Night Over Water'' is a fictionalized account of the final flight of the Pan American Clipper passenger airplane during the first few days of World War II, early ...

'', several of the main characters are BUF members. In his book ''Winter of the World

''Winter of the World'' is a historical novel written by the Welsh-born author Ken Follett, published in 2012. It is the second book in the ''Century Trilogy''. Revolving about a family saga that covers the interrelated experiences of American, ...

'', the Battle of Cable Street plays a role and some of the characters are involved in either the BUF or the anti-BUF organisations.

* The BUF also appears in Guy Walters

Guy Edward Barham Walters (born 8 August 1971) is a British author, historian, and journalist. He is the author and editor of nine books on the Second World War, including war thrillers, and a historical analysis of the Berlin Olympic Games.

...

' book ''The Leader'' (2003), in which Mosley is the dictator of Britain in the 1930s.

* The British humorous writer P. G. Wodehouse

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, ( ; 15 October 188114 February 1975) was an English author and one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century. His creations include the feather-brained Bertie Wooster and his sagacious valet, Jeeve ...

satirized the BUF in books and short stories. The BUF was satirized as "The Black Shorts" (shorts were worn because all of the best shirt colours were already taken) and its leader was Roderick Spode

Roderick Spode, 7th Earl of Sidcup, often known as Spode or Lord Sidcup, is a recurring fictional character in the Jeeves novels of English comic writer P. G. Wodehouse. In the first novel in which he appears, he is an "amateur dictator" and the ...

, the owner of a ladies' underwear shop.

* The British novelist Nancy Mitford

Nancy Freeman-Mitford (28 November 1904 – 30 June 1973), known as Nancy Mitford, was an English novelist, biographer, and journalist. The eldest of the Mitford sisters, she was regarded as one of the "bright young things" on the London ...

satirized the BUF and Mosley in '' Wigs on the Green'' (1935). Diana Mitford

Diana, Lady Mosley (''née'' Freeman-Mitford; 17 June 191011 August 2003) was one of the Mitford sisters. In 1929 she married Bryan Walter Guinness, heir to the barony of Moyne, with whom she was part of the Bright Young Things social group o ...

, the author's sister, had been romantically involved with Mosley since 1932.

* In the 1992 Acorn Media production of Agatha Christie's ''One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

"One, Two, Buckle My Shoe" is a popular English language nursery rhyme and counting-out rhyme. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 11284.

Lyrics

A common version is given in ''The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes'':

:One, two, buckl ...

'' with David Suchet and Philip Jackson, one of the supporting characters (played by Christopher Eccleston) secures a paid position as a rank-and-file member of the BUF.

* The BUF and Oswald Mosley are alluded to in Kazuo Ishiguro

Sir Kazuo Ishiguro ( ; born 8 November 1954) is a British novelist, screenwriter, musician, and short-story writer. Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki, Japan, and moved to Britain in 1960 with his parents when he was five.

He is one of the most cr ...

's novel ''The Remains of the Day

''The Remains of the Day'' is a 1989 novel by the Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Prize-winning British author Kazuo Ishiguro. The protagonist, Stevens, is a butler with a long record of service at Darlington Hall, a stately home near Oxford, ...

''.

* The BUF and Mosley are shown in the BBC version of '' Upstairs, Downstairs'' (2010) in which two of the characters are BUF supporters.

* The Pogues

The Pogues were an English or Anglo-Irish Celtic punk band fronted by Shane MacGowan and others, founded in Kings Cross, London in 1982, as "Pogue Mahone" – the anglicisation of the Irish Gaelic ''póg mo thóin'', meaning "kiss my arse". ...

' song " The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn", from their album ''Rum Sodomy & the Lash

''Rum Sodomy & the Lash'' is the second studio album by the London-based folk punk band The Pogues, released on 5 August 1985. The album reached number 13 on the UK charts. The track "A Pair of Brown Eyes", based on an older Irish tune, reached ...

'' (1985), refers to the BUF in its second verse with the line "And you decked some fucking blackshirt who was cursing all the Yids".

* Ned Beauman

Ned Beauman (born 1985) is a British novelist, journalist and screenwriter. The author of five novels, he was selected as one of the Best of Young British Novelists by ''Granta'' magazine in 2013.

Biography

Born in London, Beauman is the son of ...

's first novel, '' Boxer, Beetle'' (2010), portrays the Battle of Cable Street.

* C. J. Samson's novel ''Dominion'' (2012) has Sir Oswald Mosley as Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

in a "post- Dunkirk peace with Germany alternate history thriller" set in 1952. Lord Beaverbrook is Prime Minister of an authoritarian coalition government. Blackshirts tend to be auxiliary policemen.

* In the film ''The King's Speech

''The King's Speech'' is a 2010 British historical drama film directed by Tom Hooper and written by David Seidler. Colin Firth plays the future King George VI who, to cope with a stammer, sees Lionel Logue, an Australian speech and language ...

'' (2010), a brief shot shows a brick wall in London plastered with posters, some of them reading "Fascism is Practical Patriotism" and others reading "Stand by the King". Both sets of posters were put up by British Blackshirts, who supported King Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

. Edward was suspected of fascist leanings.

* Sarah Phelps

Sarah Phelps is a British television screenwriter, radio writer, playwright and television producer. She is best known for her work on ''EastEnders'', a number of BBC serial adaptations including Agatha Christie's ''The Witness For the Prosecut ...

used the British Union of Fascists' insignia as a theme in her 2018 BBC One

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's flagship network and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includes BBC News television bulletins, ...

adaptation of Agatha Christie's ''The A.B.C. Murders

''The A.B.C. Murders'' is a work of detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, featuring her characters Hercule Poirot, Arthur Hastings and Chief Inspector Japp, as they contend with a series of killings by a mysterious murderer kn ...

''.

* Amanda K. Hale

Amanda K. Hale is a Canadian writer and daughter of Esoteric Hitlerist James Larratt Battersby.

Background

Born in England, she emigrated to Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She studied at Concordia University and received an M.A. in Creative Writi ...

's novel ''Mad Hatter'' (2019) features her father James Larratt Battersby

James Larratt Battersby (5 February 1907 – 14–29 September 1955) was a British fascist and pacifist, and a member of the Battersby family of hatmakers of Stockport, Greater Manchester, England. He was forced to retire from the family firm du ...

as a member of the BUF.

* Mosley was portrayed by Sam Claflin

Samuel George Claflin (born 27 June 1986) is an English actor. After graduating from the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art in 2009, he began his acting career on television and had his first film role as Philip Swift in '' Pirates of th ...

in Series 5 and 6 of the BBC show ''Peaky Blinders

The Peaky Blinders were a street gang based in Birmingham, England, which operated from the 1880s until the 1910s. The group consisted largely of young criminals from lower- to middle-class backgrounds. They engaged in robbery, violence, rack ...

'' as the founder of the BUF.

* The legacy of BUF is a theme of the final episode of season 8 of the detective series ''Father Brown

Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective who is featured in 53 short stories published between 1910 and 1936 written by English author G. K. Chesterton. Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intui ...

''.

Election results

See also

*List of British fascist parties

Although Fascism in the United Kingdom never reached the heights of many of its historical European counterparts, British politics after the First World War saw the emergence of a number of fascist movements, none of which ever came to power.

Pr ...

* '' Mosley'' (1997)

* The flash and circle symbol

* Battle of South Street – an incident between BUF members and anti-fascists in Worthing on 9 October 1934

References

Further reading

* Caldicott, Rosemary (2017) ''Lady Blackshirts. The perils of Perception - Suffragettes who became Fascists'', Bristol Radical Pamphletteer #39. * * * Drabik, Jakub. (2016a) "British Union of Fascists", ''Contemporary British History'' 30.1 (2016): 1–19. * Drábik, Jakub. (2016b) "Spreading the faith: the propaganda of the British Union of Fascists", ''Journal of Contemporary European Studies'' (2016): 1-15. * Garau, Salvatore. "The Internationalisation of Italian Fascism in the face of German National Socialism, and its Impact on the British Union of Fascists", ''Politics, Religion & Ideology'' 15.1 (2014): 45–63. * * * {{Authority control 1932 establishments in the United Kingdom 1940 disestablishments in the United Kingdom Antisemitism in the United Kingdom Banned far-right parties Defunct political parties in the United Kingdom Fascist parties in the United Kingdom Oswald Mosley Political parties disestablished in 1940 Political parties established in 1932 Racism in the United Kingdom National syndicalism Fascist parties